I tend to the chickens at our house as often as JR cooks dinner. Which is to say, next to never, and only as an absolute necessity of survival – either the chickens’ or ours, as the case may be.

In fact, JR usually does whatever he is able to keep me from tending to the chickens. A few years ago, JR was away for work for a week. Before leaving, he arranged to have his brother and another friend feed and “water” the animals. “Water” or “Watering” is a common term among those who keep livestock, but I’ve found that for many non-livestock possessing people, it conjures up the idea of livestock in potting soil and a watering can gracefully depositing a spray of water over them. And then it produces giggles in the non-livestock possessing members of the population. Watering, in fact, is the act of providing drinking water to the animals. Larger animals have troughs, dogs and cats have bowls, and chickens have, well, chicken waterers. Yes. That truly is their name. Chicken waterers generally have some sort of vacuum created in order to dispense small amounts of water. Apparently, chickens, left to the devices of their small brains, will drown if allowed too much water as they will push their beaks to the bottom of the reservoir given the opportunity, and then they will stay there and suffocate. Or at least this is the story I’ve been told. I imagine it could be chicken fiction, but I am living by it regardless.

Chickens don’t require a whole lot of tending to, with the exception of collecting the eggs daily, a mucking out of their quarters from time to time, and feeding and watering. If you happen to purchase a large enough feed dispenser and chicken waterer, you can avoid the feeding and watering tasks for days. When we first got the chickens, we had a very small chicken waterer, one that required filling at least once per day. After a year of that, JR purchased a larger chicken waterer, one which could be filled and left for a few days’ time before requiring a refill.

Though he had long shielded me from the chicken-tending, JR had an overnight work trip which corresponded with his brother’s vacation and a dearth of other friends available to cover for him in these duties. I understand the confusion you may have about JR not wanting me to deal with the chicken chores as a.) I live at the house so isn’t it easier for me to take care of the chickens rather than have someone drive over here to do it?, and b.) how difficult can it possibly be to feed and water twenty or so chickens?

JR generally leaves for work between five and six o’clock in the morning, a time at which I am barely cognizant of my name. To review my chicken responsibilities, he called me later in the morning that was to be his night away – I’m not certain why we didn’t have the foresight to review the chicken watering prior to him leaving, but suffice it to say, we didn’t. He began to describe in detail how to work the new, larger chicken waterer before telling me that the chickens were almost certainly out of water, and as it was the middle of summer, they would need the water before I left for work. Again, I’m not certain why the waterer wasn’t filled while he was still home, but, again, it wasn’t. Now, I am not a morning person, and as he described how the waterer worked, my eyes, still crusted over with sleep, wandered about the room, thinking of what I needed to do to get ready for work, what ridiculousness would ensue when I got there, when JR would be home, and what we would have for dinner when he returned. All of the important stuff, basically. Then I heard, “you got all that?” “Yeah, yeah, yeah,” I said, “sounds like a pain in my ass.” As I mentioned, I am not a morning person.

Dressed for work, I approached the chicken coop, which is more like a palatial chicken mansion in its size. In fact, it is larger than my kitchen. I think I’ll need to address that with the chickens and JR, now that I’m thinking of it. In any case, I shooed the chickens away from the door as I entered, retrieved the chicken waterer, and carried it to the French drain in the barn. The water is supplied by an old-fashioned pump, one which consists of a pipe as tall as I am, and a level that you pull up to release the water. Attached to the pipe is a hose, which I positioned in the chicken waterer. I lifted the lever, and watched as the hose sprayed out of the waterer, leaving water everywhere on the floor nearby the French drain, though not in the French drain, and, while this is in the barn, it happens to be in the part of the barn that is my studio. I swept the splattered water into the drain, and then made a second attempt. This one was successful, and so I screwed the cap onto the waterer. I mentioned before that chicken waterers involve a vacuum, so the cap is also the bottom of the waterer once you turn it over – it has a ridge around the circumference to contain the water and protect the chickens from certain death by drowning. I flipped the waterer over while still in the studio so that I could carry it by its handle. At this stage, the water should reach its level and then cease to drain as there is a vacuum at work. However, I had missed a critical bit of information in the phone lesson on the waterer, and so I had not sealed the opening that would create a vacuum. Instead, I watched as the water poured all over the floor, putting to shame the relatively small amount of water sprayed by the hose moments earlier.

I flipped the waterer back over, and called JR in a panic. He walked me through the chicken waterer operation once more, I created the vacuum, and was able to transport the waterer back to the coop without any significant loss of water.

JR returned the next night and promptly went to attend to the chickens. He found them standing around a dry waterer-moat though the very large reserve was full of water. I had neglected to remove the vacuum-sealing cap, and had left the water unable to drain into the reservoir, so the chickens had been without water for nearly two days. “I knew it sounded like a pain in my ass,” I replied when confronted with the fact that I had nearly killed the chickens by depriving them water.

Today it is snowing profusely. I shoveled the deck, made my coffee, drank a cup, and came back out to find the deck as snow-covered as it was before I had shoveled it. I have been carrying wood from the wood pile to the house, stocking up for the storm, and battling with seemingly non-flammable kindling in the studio stove. And, I have been tending to the chickens. JR worked thirteen hours yesterday, and as soon as he arrived home, we went to our neighbor’s house for a holiday get-together. The chickens were out of food, and in the winter, the water freezes, so it has to be changed daily. Luckily for the chickens and for me, because of the freezing problem, we use the smaller waterer so that we don’t end up with a large block of ice that would take days to melt as it would with the larger waterer.

I poured feed into the feeder and onto their heads while trying to pour it into the feeder. I then removed the waterer and brought it to the house to defrost enough to open and refill. When I returned to the coop, there were two eggs in the nesting boxes. Nesting boxes are just as they sound, boxes made for the chickens to lay eggs within and to set upon if the eggs are fertilized. You don’t need a rooster to get eggs, a rooster is only necessary to fertilize eggs – and also to come flying across the backyard, talons first, to scratch the hell out of your legs if he thinks you’re coming too close to his girls. You’d be surprised at the horizontal jump a rooster can muster when he feels it necessary. We no longer have a rooster, and, while I wish I could say that it was because he did scratch the hell out of my legs, instead, he met a tragic end in the jowls of some nasty neighborhood dogs. Nonetheless, we still have chickens, and the point is that they don’t need a rooster to provide eggs. I put the first egg in my pocket. It was quite cold. I had seen it there when I went in the first time to dispense the feed and collect the waterer, and in this weather, it wouldn’t take long for its temperature to drop to near-freezing. The second egg was piping hot. And by piping, I mean around the body temperature of a chicken.

I had had this experience once before, the experience of holding a just-laid egg in my hand moments after it had come out of the chicken. Long before we had the chickens ourselves, JR and I went to Antonelli’s Poultry on Federal Hill in Providence. It’s a rough place if you don’t want to know specifically from where your food comes. The front is a small, narrow store-front, with pantry staples, some vegetables, and meats. Walking past the cash register, you come to a plastic door, which, if you’ve worked in a restaurant, would be familiar to you as the liner to the walk-in refrigerator. Once you pass through the plastic door, you enter into a room with cages and cages of chickens, ducks, and rabbits. You take a number just as you would at the deli counter, and when it’s your turn, you either select an animal for your dinner, or you tell them what type of animal you’d like and around how much you’d like it to weigh, dressed out. The slaughter man then takes care of the killing, draining the blood, gutting, feathering, and rinsing, and within just a few minutes, you are in receipt of that night’s dinner. It doesn’t get much more fresh than that. As you might imagine, not many people have the stomach to source their poultry in this fashion, but it’s worth doing just once if you want a full appreciation of what it takes to get a chicken into the pot. During this visit, a chicken laid an egg as its cage was being moved. One of the workers reached into the cage and held out the egg to me. I held it for a second, warm as it was, with a little mottling on the brown shell, and then reached to hand it back. “No. No. For you,” he said. And I carried it around with me while we continued to shop in the neighborhood’s Italian markets. We ate it when we arrived home, and it was delicious. But to that point, I hadn’t ever considered eggs as anything more than a convenience and a staple. Knowing that a chicken had just laid that egg – and that the chicken was likely not to be alive for another day – made the egg that much more incredible.

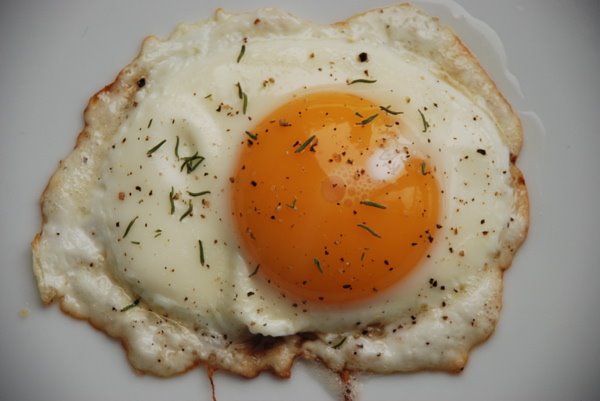

I took the warm egg from the coop, and went promptly to the house. I melted some butter in a fry pan, cracked the egg, and started to cook it before it had a chance to cool. There is the saying that the one hundred folds in a chef’s toque represent the mastery of the one hundred ways to cook eggs. And I’m just happy to have this one perfect fried egg on this snowy day, the last one before the new year. A year during which I hope to master a few more preparations of fresh eggs, and one during which I plan, among other things, to be a better chicken husbandress.

Ingredients

- 1/2 tablespoon unsalted butter

- 1 large, fresh egg. Preferably still warm, if you can find one such.

- salt

- pepper

- thyme or fennel seed, or any other herb of your choosing

Instructions

- Over medium heat, melt the butter in a small frying pan. Crack the egg into the butter, and reduce heat to medium low. Cook until egg has reached desired doneness. You must pay attention to the egg if you want a runny yolk, so don't stray too far from the stove. Salt and pepper to taste. Sprinkle a favorite herb over if you so desire. Serve at once.

Dinner tonight: Lamb Shanks in a Simple Gravy with mashed potatoes and carrots. Estimated cost for two: $19.50 for a holiday celebration meal. We will also be having Champagne that I purchased at an end-of-bin sale last January. Keep your eyes open for end-of-bin sales – you can get some good bargains on fancy wines at those bad boys. The lamb shanks were $8.43. The wine I will use was $7.99, and I’ve had a glass out of the bottle, so we’ll call the cost of wine $5.35. I am using turkey stock made from the carcass of the turkey-in-a-hole-in-the-ground, but if you were to purchase stock, it would be around $2.19 for 4 cups. I think you’d only need 3 cups, however, so that’s a cost of $1.64. I’ll use mustard, which won’t be more than 20-cents’ worth, and oil at around 80-cents. The flour will be negligible, but let’s call it 20-cents as well. Potatoes are 57.5-cents per pound, so we’ll call that 58-cents. Butter will be around 70-cents. The carrots were $3.99 for 5 pounds, and let’s say we’ll use a pound, though it will probably be less, and that total is 80-cents. I’m thinking that I may make a custard for dessert, now that I’m embarking on an egg-preparation-mastery quest, but we’ll see about that.